Preparing for a Passover Seder was a major project. All of us had our special tasks. Granny and Mom cooked; I helped to set the table, placing a Haggadah (a book of Passover stories, prayers and songs) at each seat. My aunts each brought a contribution to the Seder meal. And Zaide prepared the "bitter herbs" - the horseradish.

I can still close my eyes and see Zaide standing at the kitchen sink, an apron around his waist. His left hand gripped a grater, cradled in a large bowl; his right hand held a fresh horseradish root. It was a tedious job, and a disagreeable one - the volatile vapors of freshly grated horseradish root are far stronger than onion. Tears streamed down his face. But those tears could not wash away his smile. This was his job - his contribution to the Seder preparations - and he did it gladly.

Granny's special task was to prepare a much gentler ritual food - the Charoset. She put wedges of apple and a handful of freshly shelled walnuts into a wooden bowl that had grown old in Passover service. She chopped the apple and walnuts into a fine paste, then added cinnamon, honey and sweet wine made especially for Passover by Uncle Edel.

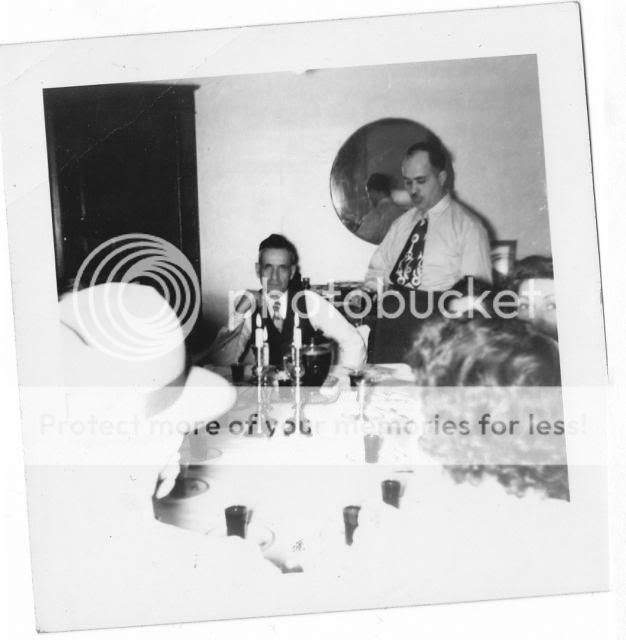

Excitement built as the family arrived and sunset neared. Twenty of us - adults and children - settled noisily into our places, chattering greetings and catching up on news. Silence fell when Granny stood to bless the candles at sunset to mark the start of Passover. Zaide took his place at the head of the table, lifted his cup, and began the Seder with a blessing over Uncle Edel's sweet wine. Uncle Moe, seated at Zaide's left, rose in turn to recite the same blessing, followed by each of the men at the table.

|

| Zaide seated at the head of the table, listening to Uncle Moe recite blessing over wine. |

Finally, it was my turn. I stood, Haggadah in hand (even though I knew the words by heart) and began to recite in Hebrew "Why is this night different from all other nights?"

As I sat down, Zaide picked up his Haggadah, looked at his family gathered around, and began to recite the answer, "We were slaves in Egypt ...." I watched him as he read and, even from my seat at the far end of the table, I could see tears gathering in the corners of his eyes. Tears of joy. Tears of pride. Tears of love.